Photographs by Mac Kilduff

When Malcolm X founded the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU) in 1964, he ended the group’s Statement of Basic Aims with the following quote: "Armed with the knowledge of our past, we can with confidence charter a course for our future." Simply put, we (humanity, that is) must know where we've been in order to know where we're going.

The meaning of the phrase holds particular significance in light of the recent tragic shooting death of veteran and father of four Walter Scott. Sadly, Scott met a fate that is and has been all too commonplace for many African Americans when he was gunned down by now former North Charleston police officer Michael Slager. Despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary, many people view Scott’s death as an isolated incident. They see Slager as just one bad apple. They don’t understand why people are continuing to protest after he was finally arrested. My challenge to them is to study their history. In doing so, they’ll find there has pretty much never been a time in the history of black Charleston when police brutality, racial profiling, and vigilantism hasn't been an issue.

Charleston became the richest city in colonial America as a result of exploiting enslaved Africans to clear land, raise livestock, and cultivate labor-intensive crops, among other tasks. So many enslaved Africans were brought through the ports of Charleston that about half of black America today descends from someone who passed through here. White slave owners amassed great wealth in a relatively short period of time and soon found the need to protect their economic investments. This was especially true in the aftermath of the African-led Stono Rebellion of 1739. Numerous white plantation owners and their families were killed before a white militia gathered to quash the revolt. The following year, the infamous 1740 slave code, or “Act For The Better Ordering And Governing Of Negroes And Other Slaves…,” was passed to severely restrict social and economic progress of enslaved Africans (and indigenous Americans). After slavery, similar laws were passed in the form of “An Act To Establish And Regulate The Domestic Relations Of Persons Of Colour…,” otherwise known as black codes. Regardless of the name, their purpose was the same—to control the lives of the African Americans. South Carolina’s slave and black codes were of particular influence since Charleston had been such a major player in both the transatlantic and domestic slave trade. In many cases, states across the South took their lead from South Carolina and adopted similar laws to control the lives of blacks. Throughout history, slave patrols, all-white militias, and terrorist groups like the Ku Klux Klan helped enforce legally sanctioned black marginalization and oppression through intimidation and unspeakable violence. What many Americans often do not realize is that these groups formed the basis of this nation’s first police forces.1

Thus, by examining the history of policing in the African American community, one quickly realizes that the issue of police brutality against blacks is by no means a new occurrence. What is new, however, is the way in which social media has allowed those seeking justice to shed light on an on-going issue that has not always has the attention or interest of the mainstream media or status quo. In 2015, a black person has died at the hands of police once every eight hours. The statistics are appalling at best. The question is what are we going to do about it? Firing and arresting former officers like Slager is a superficial solution to a deep-rooted problem. Slager shot at and killed an unarmed African American, handcuffed his dying body, and proceeded to plant evidence and lie about what took place. What stood out to me about the situation was his initial confidence. It’s clear to me Slager was confident in the fact that the other officers on scene would either corroborate his story or consent with their silence. He was confident that his version of the events would be accepted as fact. This, in my opinion, must stem from a pre-existing culture within the North Charleston Police Department (NCPD) in which racial profiling and the use of excessive force against people of color is condoned and maybe even encouraged. Sacrificing Slager won’t solve this issue, though on some superficial level, it may appease the masses (i.e. those who are either too uniformed or blinded by their own privilege to actually care the issues before us). Body cameras are a step in the right direction, but they’re not a cure-all either. If meaningful change is going to come, there needs to be, at the very least, an investigation led by the US Department of Justice into the culture of the NCPD. Hopefully this will identify the root of the issues leading up to this tragedy and help reassure the public, particularly those impacted most by this, that serious measures are being take to address these longstanding issues.

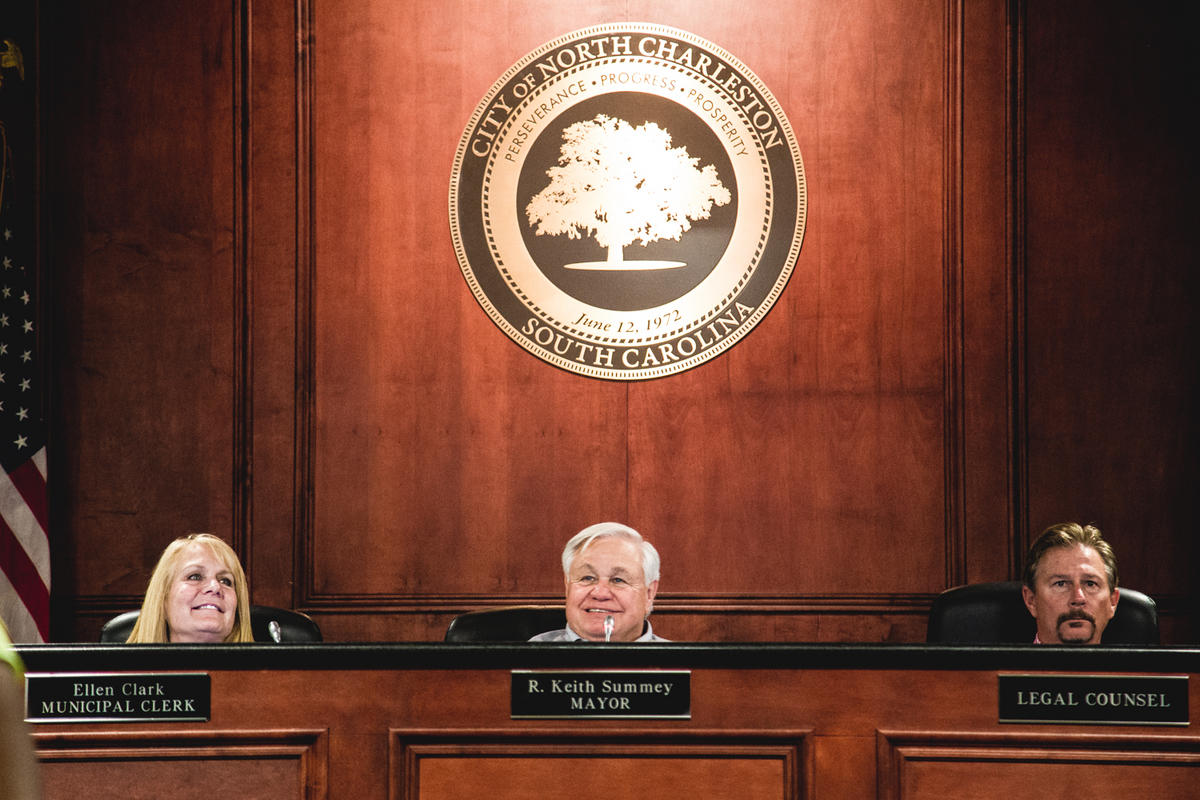

Last week, as the mayor of North Charleston, Keith Summey, stammered his way through a press conference immediately following Slager’s arrest, he said something very poignant—he looks at the officers in his city as his own children. Well, Mayor Summey, children learn intolerance and prejudice from their parents. It’s time to clean house.

[1] http://www.teachingushistory.org/pdfs/Transciptionof1740SlaveCodes.pdf;

http://www.sagepub.com/upm-data/50819_ch_1.pdf