Every year I get excited about National Hispanic Heritage Month, which lasts from September 15th to October 15th. As an African Studies enthusiast, I learned a long time ago that the overwhelming majority of enslaved people brought from Africa during the Trans Atlantic Slave trade ended up in Hispanic colonies throughout the Caribbean and South America. So for me, Hispanic Heritage Month represents another opportunity to celebrate and uplift black history on a national scale, similarly to how it’s done in February for African American History.

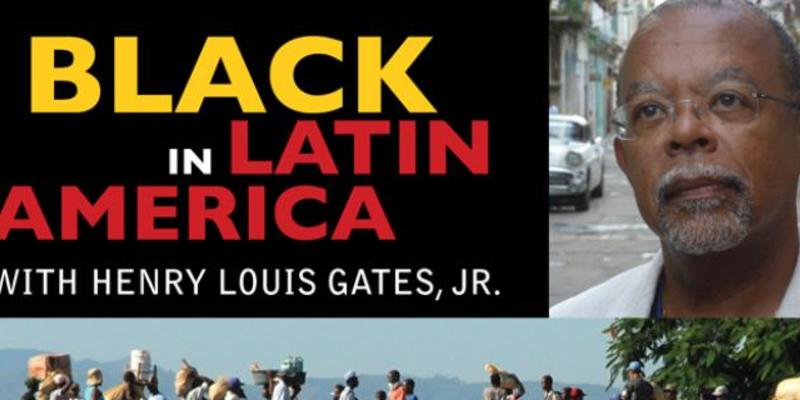

One of the ways I like to promote Afro Hispanic heritage is by sharing episodes of my favorite miniseries on my social media pages. I discovered the Black in Latin America series from PBS on Youtube a few years ago and fell in love.

In the series, host Henry Louis Gates travels throughout the Caribbean, Central and South America to uncover what it means to be black, i.e., of African descent in places like Dominican Republic, Haiti, Cuba, Brazil, Mexico and Peru. Growing up between California and South Carolina, visiting family on the Gulf Coast and having studied abroad in both Spain and France, I have had the opportunity to get to know people from all over Latin America. One of the things that always struck me, particularly after I became more aware of the lasting impact of slavery/white supremacy, was the level to which anti-blackness permeated the Hispanic community.

I’ve met a number of black people from Spanish speaking countries who completely deny having any relationship to Africa or being black, in fact they found the idea insulting. In my experience, black people in Latin America tend to identify themselves by their nationality, e.g., Panamanian or Dominican, rather than their ethnic origins or race. I’ve had Afro Hispanic people say to me, “In my country you’d be considered white.” This was so difficult for me to understand as an African American who grew up accepting the “one drop rule” as fact.

In the United States, if a person has one drop of African blood, said person is classified as black. Though we too have internalized negative perceptions of Africa and blackness as a result of living in white supremacist society founded on slavery, African Americans still recognize that we are members of the so-called black race and we come in all shades, from blue-black to light-bright, damn near white and everything in between. Having been socialized this way, I didn’t understand how a black person in Latin America, who looked just like me or someone in my family, could be classified as anything other than black. Apparently, Dr. Gates wanted to get to the bottom of this as well.

In episode one of Black in Latin America, Dr. Gates explores the Dominican Republic where there is also a “one drop rule.” Like many former Spanish colonies in the Caribbean, the Dominican Republic had a relatively small white population throughout history. Yet, according to the racial hierarchy of the times, whites citizens were needed to monopolize administrative positions in the colony. However, due to the shortage of whites on the island, ethnically mixed people were encouraged to identify as white in an effort to keep the upper echelons of society as white as possible. Therefore, in theory, having a drop of European blood meant one could identify as white and if not exactly white, there were a variety of other terms adopted by mixed blacks, all of which were meant to promote one’s non-African ancestry. Thus, the term black or ‘negro’ was reserved for those of (mostly) pure African descent who occupied the lowest rungs of Latin American society. Understanding this concept helped me make sense of the many arguments I had with Afro Hispanic associates and Hispanic people in general about race/ethnicity over the years.

Despite the fact that people of African descent have made and continue to make significant contributions to Latin American society, Afro Hispanic identity is rarely celebrated for what it is. For many people, when they think about a Hispanic/Latino person, whether from Puerto Rico, Panama or Peru, the image they have in their head is of a white person or even an indigenous person, but rarely a black person. The more I explore Afro Hispanic history, the more I have come to realize that people of African descent in Latin America experience the same type of marginalization and oppression as their African American counterparts.

Mexico, for example, had an enslaved African population nearly equal to that of North America, yet black Mexicans have been all but ignored by Mexican government. To this day, Afro Mexican communities are some of the poorest in the country, lacking infrastructure, basic sanitation, and educational and professional opportunities. Black Mexicans also face blatant discrimination when they leave their communities. There is a widely held belief that there are no black people in Mexico. As a result, black Mexicans are often harassed by police who assume they’re illegal immigrants. Often they’re forced to show proof of citizenship or even made to recite the Mexican national anthem. As a result of this type of treatment, black Mexicans choose not to venture outside of their communities much. Many suffer in silence.

For these reasons and more, I take Hispanic Heritage Month as an opportunity to shed light on the stories of Afro Hispanic communities, their contributions to society, and their struggles therein. In the era of black lives matter I believe it is important to bridge the gap between communities in the African Diaspora and expand our understanding of the black experience. History has proven that if we don’t share our stories and uplift each another, no one will.