As someone who studied the modern civil rights movement rather intently as a graduate student, I’ve often found myself wondering what happened to it. This has been especially true with the emergence of a younger generation of activists centered on protesting racial profiling and police brutality, among other things. Interestingly enough, I wrote my master’s thesis on Charleston native and civil rights activist James Eber Campbell. Campbell was a revolutionary educator. During the 1960s, his work helped pave the way for the emergence of African American Studies as an academic discipline. So I’m not at all surprised that it was he who led me to my answer. Campbell remains very active in the Charleston community and, in celebration of his upcoming 90th birthday, has been leading a monthly discussion group on the 2010 book Climbin’ Jacob’s Ladder: The Black Freedom Movement Writings of Jack O’Dell. O'Dell and Campbell were roommates in 1960s Harlem, and both men were extremely active in the movement. For our first assignment, Campbell asked us to read O’Dell’s 1978 article “On the Transition from Civil Rights to Civil Equality.” O’Dell began by asking the very question I’ve recently been asking myself: “What ever happened to civil rights?”1

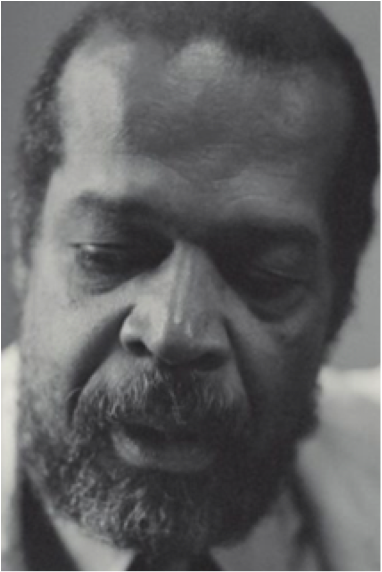

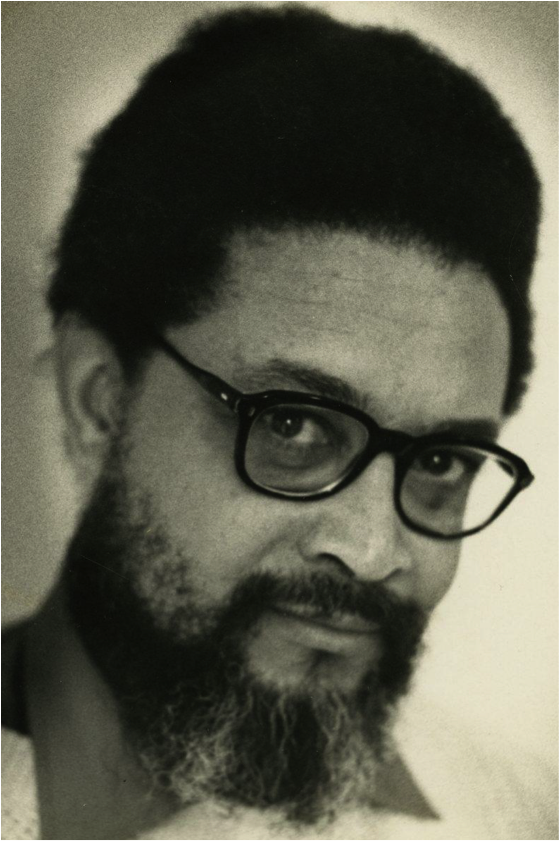

Jack O'Dell (l) and James Eber Campbell

To answer this question, O'Dell first points out the importance of recognizing that the civil rights movement was a part of a longstanding social movement in America, the black freedom struggle, reaching back to the first organized forms of resistance to slavery led by blacks themselves, from the Stono Rebellion to the Denmark Vesey Conspiracy. O’Dell goes on to add that civil rights has many characteristics in common with other movements in the black freedom struggle. O’Dell points specifically to activism of the World War I era as a more direct root of civil rights. Black veterans played key roles in advocating for black enfranchisement and equality. As far back as the Revolutionary War, African Americans have used military service as a bargaining tool to achieve civil equality. So much so that in the aftermath of WWI, black soldiers and civilians became the target of white mob violence. Black veterans across the country were lynched en masse, many while still in full military uniform, because they were seen as a threat to the status quo. Black veterans faced similar obstacles during WWII, and again they continued to advocate for equality as racial tensions boiled over. It was out of this dire situation that the civil rights movement emerged.2

O’Dell went on to point out that, as is the case with most grassroots movements, the success of civil rights was, in many ways, measured by the “legislative manifestation” of activists’ demands. For example, the Civil Rights Acts (1964–65) and the Equal Rights Amendment (1972). Yet, he goes on to add, there is a substantial difference between the achievement of civil rights and that of civil equality. O’Dell uses the landmark case Brown v. the Board of Education to make his point. The movement for quality education in black America was just that. Yet, aided by biased media coverage, the goal of achieving quality education for black children shifted to one of achieving “racial balance.” The sudden focus on integration versus educational quality, according to O’Dell, essentially undermined the success of the movement by distorting its original purpose and objective. In the case of the civil rights movement, the ratification of the laws mentioned above led to a widespread belief that racial problems in America had been solved when, in actuality, they continued to worsen. Black communities in urban centers across the US suffered from overcrowding, unemployment/underemployment, substandard housing and schools, and an overall lack of political voice. Instances of police brutality continued to rise during this time period as well, and black America became increasingly more disillusioned with civil rights. For many, the concept of black power became a psychological anecdote. An extension of civil rights, black power is often thought to be one of the “most important, politically active and successful periods” in the history of the African American experience. Though there has been a historical tendency to distort the meaning of black power, it represented the black community redefining the African American experience on their own terms. During this era, we see the emergence of black studies and the black arts movement, as well the development of Hispanic, women's, and gender studies. Though its advocates successfully helped shed the legacy of white supremacy and patriarchy in US institutions of higher learning, like civil rights, black power also had its shortcomings. So what does all of this mean for the current wave of activism in America? O’Dell warns us to stay on “offensive” and always maintain “clearly defined goals” because illusions are often created to confuse, mislead, and outright “deceive the public.” Thus, as we mobilize our communities in our efforts to hold our leaders accountable, it is important that we be vigilant and avoid being distracted by attempts to delay or deter progress. We must also be flexible and willing “to regroup around the definition of what the next stage of mass democracy is and move on to its fulfillment.”3

Activists today are using social media to connect across a much broader base than ever before. They’re poised to help bring the United States, which continues to fall behind developed nations of the world, into the promises of the twenty-first century. As such, it is important to understand the difference between having the right to quality education, housing, and healthcare, to not be racially profiled, and so forth, and actually exercising those rights in day-to-day life. In 2015, African American men, women, and children have been killed in officer-involved shootings at a rate of about one every eight hours. Most recently, the highly publicized death of an unarmed African American, Freddie “Pepper” Gray, who died under mysterious circumstances while in police custody, has led to widespread uprisings across the city of Baltimore. As protests, rallies, and other forms of organizing across the country continue to take shape it is more important now than ever that activists and organizers learn from past movements, their strengths, and weaknesses. This is much more than just a moment of civil unrest, this is a movement—black lives matter.4

1 Erica Veal, “Charleston’s Own Black Shining Prince: James Campbell and the Evolution of Black Studies (master’s thesis, College of Charleston), 7.

2 Nikhil Singh, ed., Climbin’ Jacob’s Ladder: The Black Freedom Movement Writings of Jack O’Dell (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010), 222; 225; 232; Charles D. Chamberlain, Victory at Home: Manpower and Race in the American South During World War II (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2003), 4-5.

3Climbin’ Jacob’s Ladder: The Black Freedom Movement Writings of Jack O’Dell, 226-7; 231; 234-240; 253; Peniel Joseph, Waiting ‘Til The Midnight Hour (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2006), xiii; 5-6; 142; Hampton and Fayer, Voices of Freedom, xiv; xxiii; William Van DeBurg, A New Day In Babylon: The Black Power Movement and American Culture, 1965-1975 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), 31-32; 51; Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton, Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in Black America (New York: Vintage Books, 1967), 37.

4 Churchill, Ward and Jim Vander Wall. The COINTELLPRO Papers: Documents From the FBI’s Secret Wars Against Dissent in the United States (Cambridge: Southend Press, 1990).